Recently, I’ve been interviewing for a number of roles requiring experience with low level systems programming and C/C++. During the process of preparing for these interviews, I often found it quite difficult to get the right resources and knowledge. There seems to be a lot of knowledge on the internet about how to prepare for general software engineering interviews but not a lot on how to prepare for interviews that emphasize systems programming and C/C++. Hence, I’m going to use this blog post to aggregate some of the resources I found helpful during my preparation and provide my own insight into the knowledge I believe is important.

You might now be wondering how I’m even qualified to talk about this. Well, I’ll be honest, I’m certainly no expert on these topics (yet). Heck, even the great Bjarne Stroustrup, the grandfather of the C++ programming language, said he rated himself at about seven out of ten in terms of his understanding of the language. So my goal here isn’t to make the reader an expert. Instead, I hope to help an individual with decent programming experience build a road map on how to transition into a systems programming role using C++. To that end, I believe I have enough experience over the past two years interviewing at various tech companies to confidently talk about this topic at length. Hence, I’ll be using this post to summarize my process for preparing for these roles and the tidbits of knowledge I came across during this process. Note that I’ve tailored this post to be most relevant for people aiming for roles as junior/intermediate engineers so I won’t be discussing topics such as leadership/behavioral skills and knowledge on high level design patterns. Furthermore, I also won’t be discussing the common algorithm and system design preparation that is recommended for most general software engineering interviews; I found there are plenty of guides on these topics online already. Instead, I’ll be touching on four areas that I feel are often overlooked during preparation and how I went about studying for them. These four areas are General C/C++ knowledge, multi-threading concepts, debugging skills and domain knowledge.

General C/C++ Knowledge

I know it frustrates a lot of experienced developers when both C and C++ are placed in the same category as far as skills go. This is understandable as C does not contain a lot of the abstractions with regards to memory management and OOP that is common in C++. Nevertheless, I believe that having a good foundation on both languages can be immensely helpful on the job and for tackling these interviews.

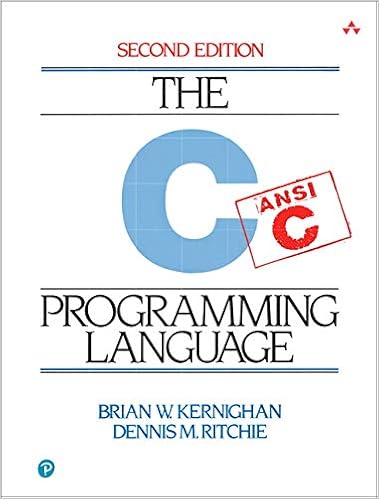

The most definitive resource for getting a solid foundation of C is The C Programming Language or simply known as K&R on account of the authors Brian Kernighan & Dennis Ritchie. Although, this book is nearly 30 years old now, C hasn’t changed all that much since it’s release so it serves an invaluable resources for the fundamentals of the language with comprehensive code samples that actually work on the first try (you think I’m kidding but this is more than I can say about a lot of modern programming books these days). I think the book is short enough such that it can easily be read cover to cover. However, where it truly shines is in the problems at the end of each chapter.

In addition to K&R, I found there are a couple other additional topics in C that require some emphasis. The first of these topics is bit manipulation. I found that oftentimes, interviewers expect candidates to know how to easily set, reset and read bits from specific registers/memory addresses along with some basic bit twiddling hacks. I suggest reviewing the following Stanford Article on some neat tricks as well as doing the top rated bit manipulation problems on a platform like Leetcode in preparation for these types of questions. Other C-based concepts I found that come up during interviews is the difference between big endian and little endian systems, the size of basic data types, representations of signed/unsigned numbers using 2’s complement and floating point representation. To better understand floating point in particular, I found that this Wikibooks article to be a good introduction to the topic along with this article, which contains a good discussion on the issues around floating point precision. In terms of data type size familiarity and endianness, I found that these topics become especially important if you are asked to code up a solution for a problem on your personal system. For example, one situation where this consideration really came to bite me was when I made the incorrect assumption that the char datatype is unsigned on all platforms during a live coding interview. Turns out, the signedness of the char datatype is actually “implementation defined” and macOS explicitly chooses to make it signed. Of course, I could have easily avoided this pitfall by simply using uint8_t from the cinttypes library but the point here is that a better understanding of the types specific to your operating system can go a long way.

Preparing for C++ interviews tends to be bit trickier than C primarily due to how expansive the language has become. I recommend two books to get a good initial foundation of the language as well as an understanding of some of the newer features added to the specification. The first is Accelerated C++: Practical Programming by Example By Andrew Koerig and Barbara E. Moo. I found that this book was an excellent introduction to iterators (chapter 5), the STL (chapters 6 & 7), template programming (chapter 8 & 9), class-based polymorphism (chapter 13) and memory management via reference counting (chapter 15). Chapter 13 is especially important as it introduces the principles behind inheritance and virtual functions, which tend to come up a lot during interviews. Similar to K&R, this book is filled with fully functional code samples and simple exercises at the end of each chapter to reinforce learning.

The second book is geared more towards understanding the new features introduced in C++11/C++14 and reads less like a tutorial and more like a reference manual. Hence, I found this book particularly dense and occasionally found myself referring to StackOverflow and various blog posts to better understand the reasoning behind some of the more sophisticated features described. Assuming that you are using this book primarily to prepare for an upcoming interview, I suggest focusing on only a select few chapters and skimming the rest. Specifically, I found that chapters 1, 2, 4 and 5 were the most useful. Chapter 1 and 2 go over the type deduction rules for C++ and discuss best practices for using the auto keyword. Chapter 4 discusses the different types of smart pointers. I suggest really understanding the internal data structures used to implement the different types of smart pointers and possibly reviewing the sample implementation from chapter 13 of Accelerated C++ for better insight. Finally, chapter 5 introduces new features around lvalues and rvalues. I found that it helpful to read this article to get the necessary background on the two value categories before jumping into this chapter.

Multithreading Concepts

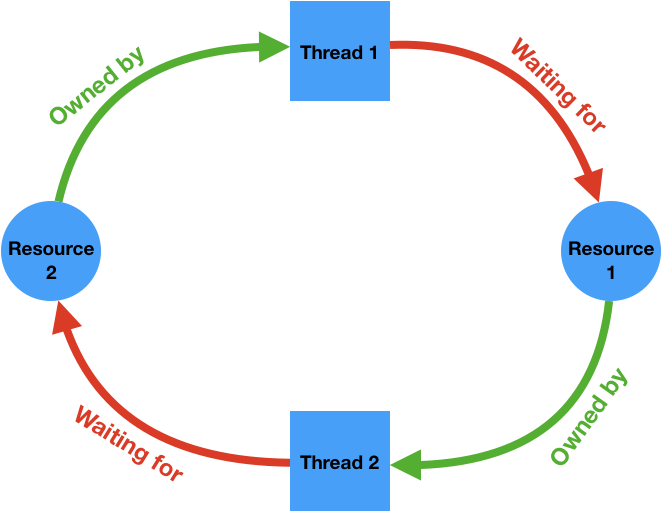

I was fortunate to have a decent background in multithreading and concurrency due to the operating systems courses I took during my undergrad. As a result, I was already quite familiar with basic synchronization primitives like semaphores and mutexes and had significant exposure to more modern mechanisms like concurrent and serial dispatch queues found in libdispatch/GCD. I also had some basic experience resolving dead locks and live locks in a production codebase, which came in particularly useful for the more theory-based problems posed during the interview process. However, I soon realized that the types of coding problems that I was assessed on tended to be more academic in nature. In order to prepare for these types of questions, I went through all the concurrency problems on Leetcode (there aren’t many) and then attempted some of the problems in the first four chapters of The Little Book of Semaphores. One basic design pattern that I found is often tested in this area is the basic producer-consumer pattern, which shows up a lot in event-driven programs (i.e. network loading).

During my practice, I’ve found that it is best to familiarize yourself with the synchronization primitives in the Standard C++ Library over other platform-specific libraries like POSIX when preparing for interviews. This is primarily because not all coding assessment platforms support POSIX so it’s best to go with the more portable library and prevent having to waste time looking up APIs during the interview. The Standard Library also has various abstractions to avoid some of the common pitfalls of multithreading programming. One example is the unique_lock, which when initialized with a mutex, automatically releases the mutex when going out of scope. Familiarizing myself with the Standard Library’s multithreading capabilities also meant that I had to become comfortable with the usage of condition variables over semaphores, which tends to be what is taught in school for thread signaling. Nevertheless, I soon discovered that both tools can be used almost interchangeably in most scenarios. A final thing to note here is that I was never asked about the more advanced synchronization features in the Standard Library such as futures, tasks or atomic objects so I don’t believe it is essential to practice using these features before an interview.

Debugging Skills

One of the most valuable skills I learned in my first job is how to debug issues in a large codebase effectively. The importance of this skill generally isn’t stressed enough in school but I suppose that is understandable as students aren’t expected to maintain a large codebase year round. Nevertheless, I found that my knowledge of this topic was evaluated in some unexpected ways during the interview process often in the form of hypothetical scenarios or in the behavioral interview. Hence, I found it useful to establish a general high-level framework for debugging some of the issues that may pop up when working on a large codebase. The two areas I have the most experience debugging is general programming errors and memory-related issues so I’ll try to outline the general systematic approach I’ve devised to tackle each of them.

I often refer to general programming errors as situations where the program behaves contrary to expectation due to a logical oversight during design or implementation. The first step when debugging these types of issues is understanding the correct behaviour and the current unexpected behaviour. Often this step requires carefully reading through the originator’s bug report and analyzing any provided logs. The log analysis often involves tracking object lifecycles to determine the state of the system during the point of failure. Occasionally, a bug can be fully diagnosed and fixed at this stage itself if one has sufficient familiarity with the problem area. However, in most cases, if this truly is a result of a programming oversight, there probably isn’t enough logging to root cause the issue at this stage. At this point, the next step is to try and reproduce the problem locally with some extra logging or with a debugger using hints from the log/bug report. If this issue is suspected to be a regression in behaviour, it is often helpful to attempt to reproduce the bug with different versions of the software and look for differences in logging to diagnose any unexpected state changes in the system. This step is often times the most laborious part of the entire process especially if the bug is a concurrency or network-related issue with a low rate of reproducibility. Once the problem is sufficiently understood and can be manually reproduced with relative ease, the next step would be to write a unit test to consistently reproduce the issue. This step can be tempting to skip but is invaluable for verifying that any code changes that you devised or was suggested during the code review actually fixes the issue at hand. The unit test also serves as a safety net to prevent future regressions and is an excellent source of documentation if at any point you have to revisit the issue at a later date. When developing the actual fix for the issue, it is important to assess the code change for risk of causing any new regressions in behaviour, which is where automated testing comes into play. However, if the fix requires altering an integral low level system component, it may still be a good idea to tailor the fix to be as minimally intrusive as possible with extra logging just in case. It may also be useful to try to relate the bug to other similar issues encountered and propose a more large scale system refactor to prevent such errors from occurring in the future.

Your effectiveness when it comes to debugging memory-related issues is dependent primarily on your mastery of the associated tooling. Using a tool such as Valgrind on Linux or Instruments and memgraphs on Apple platforms while reproducing a memory issue can be very helpful in identifying objects of interest for further investigation. One such practice I’ve engaged in quite often is logging memory addresses for objects of interest and cross correlating these addresses with a leaks or allocations trace from Instruments. This is an effective way to obtain a full retain/release history of specific segments of memory and is much easier than manually adding instrumentation to track object ownership lifecycles in a reference-counted environment. I’ve also found that being able to carefully read thread stack traces in crash and Jetsam reports to be pretty useful in quickly diagnosing some obvious memory issues (i.e. processes spawning too many blocked threads). Generally speaking, I’ve tried to employ the same procedure I use for general programming errors for memory-related issues as well with the addition of tooling.

Domain Knowledge

Domain knowledge tends to be emphasized more during the system design interview for specialist SWE roles. I found the best way to prepare for these interviews is to review any design documents or tech talks available to you to get an idea of some common design considerations behind systems of interest. For example, when interviewing for a position on a video/multimedia-related team, it maybe useful to have a high level understanding of the data flow for audio/video playback from the hardware abstraction layer to the client application on an established platform such as Android. A good operating systems background can help in understanding some of the design trade offs for these systems but areas of emphasis are usually based on your experience or the requirements for the role. For example, some concepts that came up during my interviews were different types of memory allocation algorithms, types of common hashing functions, methods for interprocess communication, network socket programming, interrupt service routines and system daemon design. I haven’t found a definitive book to prepare for all of these topics due to their somewhat disparate nature but will be sure to update this section once I come across some study resources that maybe helpful here.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/2794863-operant-conditioning-a21-5b242abe8e1b6e0036fafff6.png)